I want to take seriously a distinction that comes down to us from the Romans. We reference it all the time, but we’re too casual with it. It’s a distinction between three relational modes:

The civil - the relation between citizens, from the Latin civis.

The social - the relation between associates, from the Latin socius.

The hostile - the relation between strangers, from the Latin hostis.

For the Romans, each of these ways of relating was distinct. There could be no simple reduction to a friend/enemy distinction, as we see from followers of Carl Schmitt. For the Romans, each of these ways of relating is distinct from personal friendship (the amicus, with whom we have amiable relations) and from the declared enemy (the inimicus, the one we find inimical, the one who does not tolerate us and whom we do not tolerate).

For the Romans, it was possible to make a civis out of a hostis by first making the hostis into a socius. I’ll take you through the process by which this is done. Then I’ll compare this Roman way of first socializing and then civilizing the stranger to the way digital subjects interact online.

The Hostis

The hostis is strange to us, and therefore potentially dangerous. We do not know yet, when we meet the hostis, if we will find the hostis inimical to us. It might, in principle, be possible to establish some other kind of relationality. But to establish another kind of relationality, we need to find a common purpose - some goal or objective that we share with the hostis. It may be difficult to establish this common purpose, particularly if we do not share a language with the hostis. But, if the hostis is not inimical to us, if the hostis is also interested in having other kinds of relations with us, then it becomes possible to move beyond hostility.

When the Romans make contact with the Britons, the Britons are strange to them, but not necessarily inimical. It becomes possible for the Romans to talk to the Britons and to establish common purposes. Some of the British tribes are interested in allying with the Romans against the tribes they find inimical, and some of the British tribes are interested in trading with the Romans so as to obtain goods that are unavailable in Britain. This allows these tribes to cease to be hostis, for social relations to be established.

The Socius

The socius is our associate. We have a common purpose with the socius, but this common purpose is grounded on a kind of pragmatism. We do not love the socius for the socius’ own sake. There is no intrinsic meaningfulness to the relationship - it is not familial, it is not a kind of amity. It’s pragmatic. We do business together because we have common interests, and if we cease to have common interests then we might cease to do business together.

This means that when we deal with the socius, we are concerned about whether the socius is holding up their end of the deal. We’re worried about whether the trade is fair, whether the ally is pulling their weight. If we come to decide that the socius is not treating us fairly, we may decide to cut social ties.

It is only if this sociability is maintained over a long period of time across many different projects that we might consider the socius to be more than just a partner in a common project. We might really share a world with the socius, we might really have a thing in common that makes us more than mere associates. This thing in common, this “public thing,” would be the res publica.

The Civis

A fellow citizen, a person with whom we can be not just sociable, but civil, recognizes that our goods are inextricably linked. We want the good of the civis because we recognize that the good of the civis is tied to the common good, to the good of the public thing, the shared res publica. By committing to the res publica, the civis makes their good our good, diminishing the distinction between us and them.

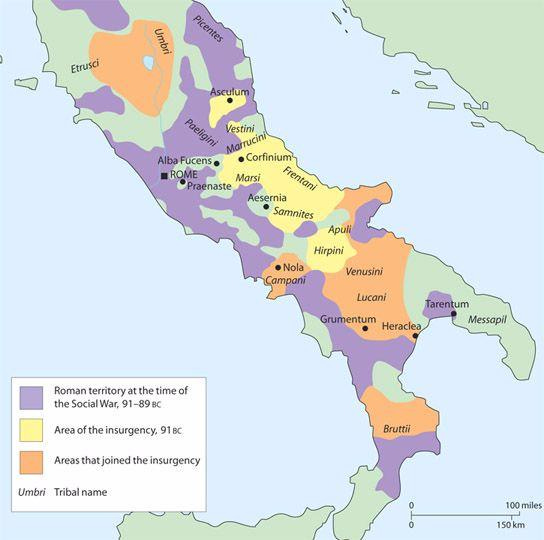

This produces a kind of relationality that is not familial or amiable but which has similar, analogous effects, in the sense that we come to want the good of the civis in much the same way that we would want the good of a sibling or a friend. In this way, the civil relation is able to produce effects that are analogous to the Greek love of family (storge) or the Greek love of the friend (philia). It induces us to view the other as intrinsically valuable, without the close personal ties that are standardly invoked in Greek narratives. The Romans were able not merely to make sociable allies of the other cities in Italy, they were able to “civilize” them, in the sense that they were able to make the people of these cities into fellow citizens of Rome. The Athenians dominated their allies through the infamous Delian League, never cultivating or recognizing a shared civility. They never achieved this level of political consciousness. When their league no longer faced a common foe in Persia, it devolved into factious enmities.

If we cannot civilize the stranger, then there is a limit to our capacity to value the stranger’s good. We cannot make everyone into a family member or a friend, and social relations are too liminal, too unstable, to give rise to the kind of tie we have with the civis. Sooner or later the common enemies are defeated, discontents arise concerning the terms of trade, and social relations regress. It is necessary not merely to establish social relations, but to go through them, to raise them to the level of the civil.

Knowledge Objects

The distinction between the civis, socius, and hostis operates does not operate merely or even primarily at the moral level. This is not purely a discussion of circles of concern or levels of empathy. It has an epistemic dimension.

The socius is distinguished from the hostis by the shared purpose. This shared purpose has to be discussed and deliberated about. We have to be able to argue with each other about what the shared purpose implies, how to go about achieving it. The shared purpose functions as a common knowledge object, orienting our discussion and giving it structure and form. When allies discuss how to defeat their shared foe, or trade partners discuss how to establish and maintain trade links and fair trade terms, the conversation is anchored by the fact that there are indeed more effective and less effective strategies and tactics available. It is in fact the case that we can do things that will achieve the shared purposes or won’t, which will achieve the shared purposes with varying levels of efficiency, in varying windows of time, at varying costs, distributed in varying ways. All of this has to be discussed, and the fact that we are discussing these specific things with the socius prevents the discussion from becoming vapid or aimless.

The shared knowledge object with the civis is the common good, the good of the res publica. But it is only possible to have civil relations when there really is a common good, when it really is the case that there is a thing we hold in common. We have to actually be part of a public. If citizens have wildly divergent interests because of, e.g., class barriers, they won’t have a common good. If they don’t have a common good, then they don’t have a common knowledge object. That means their discussion isn’t civil, even if legally or linguistically they are classified as sharing citizenship.

In capitalism, we confuse ourselves by classifying people who have different interests as citizens of the same republic. We claim these people have a common good that they can deliberate about when they don’t. We act as if there are civil relations where civil relations do not exist.

This is the sense in which, at most, the socioeconomical classes are socio, i.e., they have social relations that fall beneath the level of the civil. The workers and the employers associate with one another in the sense that they agree to work together to pursue certain shared ends. In this sense, they have society with one another. But giving the worker civil rights does not establish civil relations, it does not give the worker and the employer a common good that they can pursue together through civil discourse.

The Professional Class

What happens when the capitalist and the worker do not engage in a shared discussion about the terms of the work? In capitalism, there is a corporatising of commercial society. The relationality between the capitalist and the workers becomes impersonal and it is increasingly mediated by the college-educated professionals. These professionals do a kind of middle management. They have social relations with the capitalists, and they have social relations with the workers, but the workers and the capitalists increasingly don’t have social relations with each other, i.e., they don’t participate in a shared discussion about how to best achieve their shared purposes.

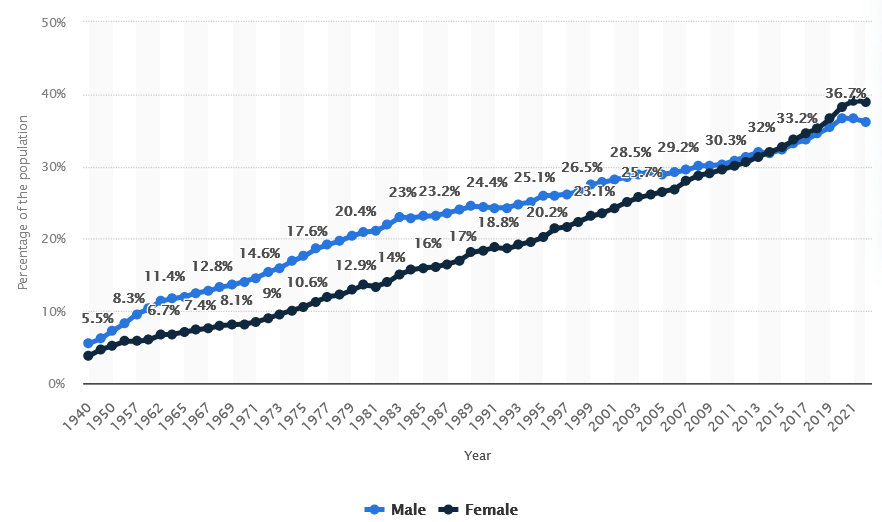

Now, in the 1940s, when the percentage of the US population with a university education was around 5%, this professional class was too small to think of itself as potentially possessing its own res publica. But as this percentage approached first 20% in 1980 and now 40% in the 2020s, it is possible for the university-educated class (or stratum, if you prefer) to take on a life of its own.

In this phase, the “new class” becomes itself divided into many grades. Increasingly, its members socialize principally with each other rather than with either the capitalists or the workers. Here are three plausible grades:

The “rump” professionals, the successful professionals who have social relations with the capitalists, and with less successful professionals, but increasingly not with the workers, whom they regard (sometimes positively, sometimes negatively) as fetishized oriental objects.

The “mid” professionals, the professionals who have social relations with other kinds of professionals, but increasingly not with the capitalists or with the workers.

The "fallen” professionals, the professionals who have social relations with workers and with “mid” professionals, but who relate to the rump professionals only in a parasocial way, i.e., they treat the rump professionals as celebrities, constructing fandoms around them.

And so, we see over the course of capitalism a series of regressions occurring:

First, the capitalists and the workers develop contradictory interests, so that civil relations between them become impossible.

Then, the capitalists and workers have their relationship mediated by impersonal corporate structures and by the professionals, so that social relations between the capitalists and the workers become indirect.

Then, the professional class grows to the point at which major parts of the professional class only have social relations with the capitalists or with the workers. Ersatz forms of sociality spread, as estranged social classes relate to each other through orientalism and parasociality.

This orientalism and parasociality is sustained first by analogue and then increasingly by digital media, which “represents” the absent social classes, allowing them to appear present. The capitalists and rump professionals think they know the fallen professionals and the workers, because they read about them or watch media about them, and the fallen professionals and the workers think they know about the capitalists and the rump professionals for the same reasons.

The “mid” professionals, who are concerned mainly with making connections between the rump and the fallen strata, delude themselves that the professional class constitutes the whole of society and can therefore be the basis for a new form of civility. They try to erect a res publica via the HR department, via the NGO, via the corporate form. This project is delusional, because it stems from an incomplete view.

The Digital Subject

Nevertheless, the intensity of the digital experience sustains forms of relationality that would have been present in Roman times, but much less central. It was possible to establish fandoms around Roman patricians, and it was possible for Roman elites to orientalize the plebeians or the provincials. It was even possible for isolated groups of Romans to think they had a grip on the civil when they didn’t - to make serious mistakes about who the emperor is. But the digital produces a kind of subjectivity in which these are not just possibilities but systematic regularities. These are not just relational modes that operate at the margins - they are dominant structures.

When we orientalize, parasocialize, or create fictive realms, we think we are engaging in forms of relationality that we are not in fact engaging in. We think we have social or civil relations with people with whom we do not have such relations. This prevents us from fully regressing into hostility, but it also prevents us from pursuing common projects together. It disables our capacity to deliberate together, and in this sense it robs us of our capacity to consciously choose ends. In this way, the oriental, parasocial, and fictive relational modes enslave us - they deprive us of the right and of the capacity to act as free citizens or even as free associates.

Can social relations be re-established or can we find some other means of establishing civility? It seems to me that if either of these things is possible, it will have to be possible through the digital. Either the digital must transition people from the oriental, parasocial, and fictive relations into the social, or these cyberrelations must give rise to an alternative civility.

The object of civilization is to discover that we share not just ephemeral common projects, but a common world. It is to return us to a one from which we emanate. The res publica makes this one temporal - it makes it appear to have being. In this way, it provides a temporal, material, theurgic route to the universal. It leads us to the one by our own projects and interests, as we understand them. Instead of normatively reproaching us for being insufficiently advanced, it begins in the projects that are of immanent value to us. Does digital subjectivity give rise to such projects? Are digital subjects capable of formulating them? Or does the digital replace these projects with pseudo-projects, with projects that permit only very narrow, very fleeting forms of sociality, with no possibility of maintaining and deepening this relationality across time?

The Millennial left was predicated on the idea that the digital could in fact produce not just sociality, but civil relations. We Millennials once believed that despite the oriental, parasocial, and fictive tendencies, new social ties could be established through the internet and politicized effectively at scale. But as the internet is itself corporatized and subjected to the various forms of professional class mediation, this seems increasingly implausible.

Without the project of the Millennial left, what’s left? The digital subject is reduced to a semi-barbarized condition, in which ersatz forms of sociality imprison people in a kind of cage. This cage neither permits the outbreak of hostility nor the resumption of the civilizing process. Instead, it holds people in a set of functional yet empty relations. This semi-barbarized, semi-socialized situation looks, in optimistic moments, like a process of socialization. In pessimistic moments, it looks like a process of barbarization. Even as a process of barbarization, it has an optimistic aspect, in so far as a resumption of hostility could in time give rise to a new social configuration. But these optimistic and pessimistic appearances fail to grasp the brutal reality of its stagnancy. It is neither a process of socialization or barbarization. It is simply a digital cage.

To be in the positive despair, the kind of despair that helps us clear away illusions and look again at what is possible, we must drop the insistence that this cage must swiftly dissolve in either direction. But this is not to say that the cage is natural, permanent, essential, or transhistorical in character. It is subject to change. The changes that take place within it come not primarily from a developing social process, but from two other things:

Political developments - to do with competition among states and among elites (i.e., between and among capitalists and rump professionals).

Exogenous events - to do with the environment, the climate, technology, and disease.

Political developments and exogenous events will alter the digital subject. Some number of us remain capable of recognizing this situation. We can engage in a common project of studying it, of attempting to understand it and to describe it. That common project permits us to establish some level of sociality with one another. This sociality is far too limited to provide a basis for civil relations. It does not, in itself, create the conditions for a res publica. Still, by sharing this discussion online, we leave open the possibility that, if new forms of sociality do develop through transformations in digital subjectivity driven by political developments and exogenous events, those new social formations can benefit from our common project and potentially become participatory in it.

This, then, is the “we” of which I speak, in this piece and elsewhere - the set of people who are committed to the common knowledge object of understanding this situation. This set of people is the set of people I am speaking to, with whom I still, despite everything, have social (albeit not yet civil) relations. It is also a “we” I invite you to join, if you are still relating to me on a parasocial level, as a fan of my work. By becoming part of Theory Underground, you can participate in the discussion and contribute to it. You can become part of this “we.”

Social Unsociability

The greatest threat to the construction of social relations comes from those who pretend to share the common knowledge object but in fact have altogether different goals. Today, many of these people are interested primarily in recognition rather than in contributing. Their goal is to extract a kind of tribute from others. This tribute is sometimes called “social capital,” but to call it “social capital” concedes too much to it. If we were engaged in a common project of recognition exchange, to an exchange of compliments and praise, that would be a kind of sociality, but it is not the kind we’re after. This is not about exchanging flatteries. It’s about attempting to understand a situation, which means sharpening our intuitions, developing our capacities. This means disagreeing, it means criticizing each other’s theories, it means having a certain amount of productive tension with one another. We are engaged in social relations - we are not necessarily friends, and we are certainly not family. This is a pre-civil project.

There will be conflict. This conflict is necessary, and it becomes functional in so far as it is contained by our common knowledge object. But people who do not share the common knowledge object will not accept the limits that object places on the scale and intensity of the conflict. They will escalate the conflict beyond sociable limits.

Those who enter into social relations only for the purposes of gaining recognition are not entering social relations to pursue a common knowledge object. They do not have the necessary psychological prerequisites for fully social relations. Instead, they are trapped in a condition of “social unsociability.” They have social intentions but are unable to carry social relations through toward any moral or epistemic (much less political) end.

Even the so-called “barbarians” were sociable enough to agree to pursue common projects with the Romans. It was this willingness and capacity to have reasonable discussions about war and trade that allowed the Romans and the tribes they encountered to develop sociality. People today who suffer from chronic recognition lack are more barbarized than the “barbarians” - they are less capable of sociality and should be recognized as strangers. The best we can hope for, in these situations, is that these people will tolerate us, that they will not find us inimical. And, unfortunately, this toleration cannot be taken for granted.

We need people who have other sources of recognition in their lives, who do not need praise from us, who do not need to be or to feel “seen” by us. Because so many subjects are underloved - because they have had to do without the love of family, the love of friends, because they relate to others primarily through orientalism, parasociality, and the fictive, it will very often be the case that many people we encounter will not be able to contribute at this time. This has to be accepted.

The Millennial left, in supposing that the digital could provide an immediate broad social base, denied the degree to which the social unsociable orientation had spread. It admitted into its organizations an enormous number of deeply troubled people. These people leveraged unearned trust to seize commanding positions in organizations and turned ostensibly political outfits into recognition machines, into uncivilized, antisocial extraction mechanisms.

If we would write for anyone apart from God, we must not repeat this mistake. We need to understand what we are doing, and that means the common knowledge object must take priority over an unthinking commitment to inclusion or expansion. It must actually be the case that would-be participants have a real, continuing capacity to contribute, materially, to our social organization.