Today I ran across a tweet by

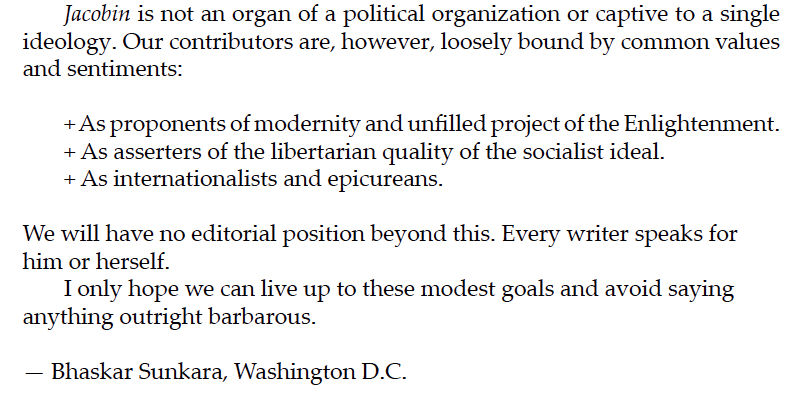

about ’s launch manifesto. That manifesto includes the following text:Tutt’s tweet focused on the emphasis on libertarian socialism (an emphasis Jacobin shared with Current Affairs - Nathan Robinson still explicitly positions himself within libertarian socialism).

But the thing that struck me was the epicurean bit. Sunkara put the word “epicurean” next to the word “internationalist”, one of the most important words in any socialist statement of purpose. He clearly wasn’t using the term in a throwaway way. What’s going on here?

Greece & India

The Epicureans were one of the three Hellenistic Schools of Greek philosophy (Stoicism and Skepticism being the other two). These three schools arose after Alexander the Great invaded India, where some of his men came into contact with the Buddhists. Scholars have taken an increased interest in the possibility of Greco-Indian (or, at later points, Romano-Indian) interactions. Here are a few recent books discussing these interactions from a variety of points of view:

Beckwith, Greek Buddha, Princeton UP, 2017

Maas & Di Cosmo (eds), Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity, Cambridge UP, 2018

Stoneman, The Greek Experience of India, Princeton UP, 2019

Seaford, The Origins of Philosophy in Ancient Greece and Ancient India, Cambridge UP, 2020

Kuzminski, Pyrrhonian Buddhism, Taylor & Francis, 2021

Kubica, Greco-Buddhist Relations in the Hellenistic Far East, Taylor & Francis, 2023

It is still a point of contention how far the Greeks were influenced by the Indians (and vice versa). There are remarkable similarities between the bodies of thought. But no one wants to claim that either is a mere product of the other - that would seem to subordinate one kind of civilization to another. This leads some scholars (e.g., Kubica) to want to defend the distinctiveness of these traditions. Personally, I tend to take the view that the bulk of the opportunities for interaction took the form of oral conversations, that a non-trivial number of these conversations is therefore likely to have occurred, and that both traditions are likely to have been affected by such conversations to a roughly equal degree. These influences would be difficult to trace in any precise way, but they would help us make sense of the fact that Pyrrho, Zeno of Citium, and Epicurus were all born within 30 years of one another and are all said to have produced their philosophies after Alexander’s Indian campaign. It seems equally likely that Platonist and Aristotelian ideas (both of which were already around when Alexander left for India) came into Buddhism and Hinduism as a consequence of this invasion and as a consequence of interaction with the Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek Kingdoms, which were active from 256-120 BC and 200 BC-10 AD, respectively. Mahayana Buddhism is agreed to have arisen during this period, though precise dates and locations for it remain contested.

To put it crudely, this would give us a picture in which Plato and Aristotle are Greek, the “Hellenistic Schools” are Indo-Greek, Theravada Buddhism is Indian, and Mahayana Buddhism is Greco-Indian (and, later, Greco-Indian-Chinese). We may never know to what degree this picture is strictly accurate at the level of history, but it is in this spirit that I’ve named this piece about the Hellenistic Schools “The Buddha’s Bastards”. The implication, of course, is that the Buddha has legitimate offspring. I am not here to pick on Buddhism (I respect Buddhism!), but only on what I take to be its reception in the West.

The Substantive Claims of the Hellenistic Schools

There are several key shifts in Greek philosophy I associate with the Indo-Greek schools. Here’s a short, non-exhaustive list I threw together just now:

An emphasis on the individual as the key ontological unit, at the expense of the notion of man as a political (or even civil-social) animal.

A concomitant emphasis on apatheia or ataraxia, i.e., freedom of the individual from disturbance, at the expense of the capacity to participate in the Good.

A highly demanding, ambitious conceptualization of knowledge, implying either that it is possible for individuals to know an enormous amount (independently of political or social factors) or that it is impossible for individuals to know anything at all.

An egalitarian tendency to regard all individuals as possessing roughly the same epistemic potential in principle (either the individual has enormous epistemic capacities or none at all).

A tendency to blame weakness of will for the failure to actualize this potential, whatever its extent.

At the same time, a fatalism about this weakness of will - the belief that it is natural that some people will fail to develop the capacity to exercise it.

These tendencies do not all fit neatly together. In practice, they are combined in various ways.

Stoicism made very strong claims about what can be known - the Stoic sage only gives assent to those cognitive impressions to which he ought to give assent, so that he is always assenting to whatever in fact occurs. Since the Stoic sage is always assenting to whatever happens, he is never disturbed by anything that occurs, and he achieves apatheia. In principle, everyone has the potential to be a Stoic sage, because everyone is endowed with a will that has this capacity. But in practice, nature has ordained that some of us are not fated to fully develop this capacity. In these cases, the best we can do is recognize that we are not sages and give assent to our deviations, which are fated. It is in this sense that a Stoic can be fated to commit suicide. In this case, the Stoic is fated not to give assent to what is about to unfold. He therefore is fated not to be a sage. But if he can assent to his fate, if he can accept that he is going to commit suicide rather than give assent, he assents to his fate in a second-order sense. This allows him to commit suicide without being disturbed by the fact that, in committing suicide, he has failed to assent to what is to come. In this way, his suicide is ennobled. Worldly goods are regarded as “preferred indifferents” - it is natural for us to prefer them, but our capacity to use the will appropriately can never be said to depend on them. Whereas for Plato or Aristotle, a good city is necessary for virtue, for the Stoics a good city is a preferred indifferent. This means that, for the Stoics, we have the same obligations in bad cities as we have in good cities - our obligations are universal in character. The greatest Stoic theoretician is widely regarded to be Chrysippus, though few of his works have survived, and we know him mostly indirectly.

The Epicureans, following Epicurus, argued that a pleasurable life is free from disturbance, provided that the practitioner chooses appropriate pleasures. Some pleasures are unsustainable and lead to suffering. The sage is discerning about which pleasures to pursue. This means that, for the Epicureans, worldly goods are necessary for ataraxia, but the sage must carefully distinguish among them. Whereas for Plato or Aristotle, some loves (psychological drives) are better or worse than others, for the Epicureans everything gives rise to pleasure, but people frequently make mistakes with regard to time-preference, choosing an immediate pleasure that will lead to a larger pain later. Again, it’s the individual’s will that is responsible for making these determinations - for Epicurus, atomistic motion is nonetheless influenced by the something called the “swerve”, through which it is possible to maintain that the will has an independent role to play in shaping what occurs.

The Skeptics, following Pyrrho, denied that anything could be known. The Skeptic sage therefore never claims to know anything. Since he never claims to know anything, he never has expectations of any kind. He is therefore never surprised and never disturbed by anything that happens. He thus achieves ataraxia. His difficulty is in not just asserting that he knows nothing, but in actually believing this, consistently, across time.

The Hellenistic Schools developed in competition with each other. Skeptical claims about the impossibility of knowledge led to boisterous Stoic claims about what would could be known, and vice versa. Claims about preferred indifferents in Stoicism led Epicureans to emphasize the importance of pleasure, and vice versa.

What it Means for Jacobin to be Epicurean

I take the Jacobin claim to Epicureanism seriously. For Epicurus, politics is something to be avoided where possible, because it involves force, and force causes suffering. Rather, individuals are able to see that pleasures become more sustainable when they cooperate socially with one another. Epicurean justice involves making compacts not to harm one another. Their enforcement, through the law, is something regrettable.

You might recognize some of these elements in the thought of, e.g., Rousseau. As we all know, the title of Jacobin suggests a commitment to French Revolutionary thought. But Rousseau was also influenced by the Stoics. He quotes them favorably all the time.1 The contemporary left prefers to associate Stoicism with the right. Current Affairs published a denunciation of Ben Shapiro that claims that “there is no Stoic political thought” - a ridiculous claim that ignores not just the Stoic influence on early modern Enlightenment thought, but also overtly political Stoics like Seneca. At one point Jacobin did publish a piece crediting the Stoics with initiating cosmopolitanism and then connecting Stoic cosmopolitanism with Kant. The piece then accuses Kant of racism, championing a “cosmopolitan socialism” purged of its Kantian elements. The Stoic influence is acknowledged but also disavowed, as part of acknowledging but disavowing Kant.

I therefore read the Epicurean commitment as an attempt to take up the Enlightenment reading of the Hellenistic Schools in a sanitized way. Because Epicureanism and Stoicism have a lot in common, it is possible for a theorist like Rousseau to be influenced by both. Yet because Stoicism is now right-coded, its influence is downplayed or disavowed. That doesn’t mean it’s not there, of course.

What about Kant Himself?

Kant framed Epicureanism as one of two kinds of dogmatism, alongside Platonism. For Kant, Epicureanism becomes a dogmatism of the senses while Platonism becomes a dogmatism of disembodied reason:

Both Epicurus and Plato assert more in their systems than they know. The former encourages and advances science—although to the prejudice of the practical; the latter presents us with excellent principles for the investigation of the practical, but, in relation to everything regarding which we can attain to speculative cognition, permits reason to append idealistic explanations of natural phenomena, to the great injury of physical investigation.2

In this passage Kant attributes to Platonism positions that are more properly characterized as Gnostic. Since, for Plato, our capacities depend in no small part on the kind of city we live in, political and social facts both enable and obscure understanding. The world of appearances is therefore not simply false - knowledge begins in appearances and yet is fettered by them. It is for this reason that Platonists reject Gnostic claims that matter or being are evil. What comes into being both creates the conditions for knowledge and limits the extent to which knowledge obtains. The Platonist is therefore neither a dogmatist nor a skeptic. Those categories belong more properly to Hellenistic philosophy. Platonism, properly understood, involves tarrying with the limits of being, not transcending and negating (but also not celebrating and naturalizing) those limits. It is for this reason that Platonic dialogues can end in aporia - when that happens, the implications are neither Skeptical nor Stoic. The goal is neither to show that we know nothing or that we know a lot. Knowledge in Platonism is dialectical - it is not negated by its limitations but birthed in and through them.

There are, of course, opportunities to make quick gains by developing a more assertive position. During the Enlightenment, there were spectacular scientific developments. This seemed to raise the ceiling on what could be understood through scientific exploration. It created, therefore, a Stoic temptation to assert that all individuals could, by use of scientific methods, come to possess very ambitious kinds of knowledge, and that through possessing this knowledge they could exercise an ambitious kind of freedom. As Chris Brooke puts it:

Immanuel Kant, standing at the head of the tradition of German idealism, admired Rousseau intensely. As a young philosopher, he thought that the ‘thirst for knowledge’ alone constituted the ‘honor of mankind’, but ‘Rousseau set me right’, from whom he learned not to despise ‘the rabble who knows nothing’ and to ‘respect human nature’, and the only picture that hung in Kant’s house, over his writing desk, was a portrait of Rousseau. The thread that connects their respective systems of thought, furthermore, is a Stoic thread. In the Social Contract, Rousseau describes moral freedom as autonomy, to live under a self-imposed law; the Stoics held that freedom was the power to live as you will, that only the wise were free, and that the wise were those who lived in accordance with the rational law of nature; and a notion of freedom as rational autonomy forms the innermost core of Kant’s practical philosophy, outlined notably in his Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals. What the German idealists found in Rousseau, above all, was an argument about how freedom had to have both a subjective and an objective aspect. One had to feel free, and the reasons one felt free had to relate to a plausible account of what it actually was to be free.3

In this way, Rousseau and Kant’s interventions are internal to the debate within the Hellenistic Schools. They are attempts to formulate a mixture of the elements common to the schools, avoiding the excesses of particular iterations. In Rousseau’s case, there is more Epicureanism (i.e., a more sensuous approach, anchored in feelings of pity), while in Kant’s case Stoic reason gets a stronger emphasis.

Plato and Aristotle tend to get the short end of the stick in so far as Plato and Aristotle have, by this point in intellectual history, become associated with counterreformation Catholicism, with scholasticism and Thomism. But Thomism also drew heavily upon arguments that came from within the Hellenistic Schools. As Raymond Geuss puts it:

Roughly speaking for Aristotle, if I do X and have not been externally coerced into doing it, that will be because (a) I chose to do X or (b) because I acted on some impulse. That is for Aristotle the end of the story. There is no “choosing” to act from choice or from impulse, and nothing like the modern “will” is involved in the process. The only thing Aristotle has to say beyond that is that if I am a good (“virtuous”) person I will generally choose rather than act on impulse, and the reason for that will be that I have natural aptitude to become a good person and have had the right upbringing. However, if I am a good person, I will - to put it paradoxically - have no “choice” about acting out of choice rather than impulse. That I habitually act from such choice is just what it is to be a good person. A good person, therefore, is not “free” in any interesting sense (apart from the political sense of not being someone’s slave). There is no room for “the will” or “freedom” in this construction. “The will” is constructed and introduced as a concept by the Stoics as an anti-Aristotelian invention to allow them to say something Aristotle never would have said, namely that the good person is “free.” It is thus much to be regretted that Thomas took this confused nonstarter of a concept “will” out of its context in anti-Aristotelian thinking and tried to graft it into a basically Aristotelian framework. Western philosophy suffered from the depredations of trying to make sense of the fictitious faculty “the will” until the time of Nietzsche.4

Geuss goes on to write in a footnote that there is no evil in Aristotle’s scheme, only a concept of “bad”. Evil only appears and becomes a problem once it is insisted that acting on impulse involves a choice not to choose - that’s the Stoic claim. But where I would differ from Geuss would be in raising the further point that this allows us to see the sense in which Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil is not properly a response to Plato but is instead a response to a Stoicized Platonism.

The Hellenistic Left

This tendency for Enlightenment thinkers to lump Plato and Aristotle in with the Stoics, as Thomas Aquinas had done, is repeatedly replicated by the left.5 The left prefers to take Enlightenment thinkers at their word about Plato and Aristotle so as to avoid having to read them itself. The effect of this is to incarcerate the left within the conceptual framework of the Hellenistic Schools.

You see this routinely, through e.g., the shibboleth about the “pessimism of the intellect” alongside the “optimism of the will”. Stoicism allows practitioners to invoke both fate and the will at the same time. This frequently develops in an opportunistic direction. When the left fails, it blames both overdetermined structures and weakness of will, flipping back and forth between the two depending on what seems convenient. The function of this is not to change the world or to get a grip on reality - it is to enable the activist to be able to psychologically endure endless failure. The left is, in this sense, continuously in a process of assenting to its own suicide. And, by repeatedly giving this assent, it lives, in ever more zombified form.

The right-wing Stoics (among these, the Straussians) fancy themselves to have done the left one better by being capitalist realists - by having assented not merely to a kind of political suicide, but to capitalism itself. They pridefully disdain those who remain incorrigibly radical in their politics - these people have failed to give their assent to what is fated.

At the same time, we also see Epicurean and Skeptical tendencies. The left wants to affirm all desires. It recognizes only the kinds of brakes on desire that Epicurus would recognize - harm reduction and questions of (especially environmental) sustainability. And, in its postmodern mode, it shows the influence of a kind of Skepticism that fails to take human values seriously, instead reducing them to pragmatic instruments or ironic poses. These different elements are mixed together, incoherently, because most contemporary leftists have little direct experience of Stoicism, Epicureanism, or Skepticism, but have imbibed these things through the projects of Rousseau, Kant, Smith, Fichte, Hegel, Marx, and Nietzsche, among others. And of course, many of them don’t read the moderns, either, but pick these things up from our popular culture, in which Hellenistic approaches are continuously naturalized and treated as common sense.

Socialism and the Stoic Society

In his recent response to my work in the Platypus Review, Chris Cutrone echoes these modernist readings of “the ancients,” liquidating the distinctions among them. In that piece, he emphasizes the value of “social freedom”, i.e., “the freedom of society to develop”. Here freedom is not attached to the individual, but to society - there is a replacement of the Hellenistic ontic unit with the modern concept of society. Individual freedom is conceptualized and concretized in and through social freedom. The discussion of “society” allows the Stoic emphasis on fate or nature to be subtly transformed into an emphasis on history, albeit one that can still be expressed in naturalistic terms when those seem more helpful.6

Is “social freedom” the freedom of society to develop into the kind of society in which ever more people can make choices rather than act on impulse? Or is it the capacity of society to become free from disturbances? Is social freedom Stoic? Maybe this is what the “classless society” would involve, or this is what we would have if the state were to “wither away”. For many anarchists, the principal crime of the state is that it disturbs society. For many Marxists the point of becoming political is to eliminate the need for politics.

But that’s not typically been Chris Cutrone. Cutrone argues for Lenin’s liberalism - that Lenin was committed to political pluralism. And Adorno - whom Cutrone loves - insisted that the pledge to abolish contradiction is itself ideological in character.7 Society cannot be free from disturbances but develops in and through them. To end the disturbance of society is thus to end the freedom of society to develop. Society cannot be freed by overcoming the political. The political necessarily arises in response to disturbances of whatever kind. The aim of eradicating the political is thus an attack on social freedom even if it might at the same time be construed as its realization.

A commitment to the political does not entail a commitment to the nation-state. It might entail a recognition that, in our current moment, the political has a strong tendency to take a national form. The question of how to change that - of how to set politics free from the national form - is not approached by most socialists, whose anti-Bonapartism or anti-statism too readily yields a hostility to the political and therefore to contradiction as such. This hostility to the political and to contradiction yields belief that there can be a society free from disturbances. Such a society would be frozen in time. In the moment it became free, it would cease to be free.

The escape from this is to reject the Hellenistic commitment to “freedom from disturbance” and to instead conceptualize social freedom in dialogue with the political. The contents of social freedom depend on what can be politically legitimated at any given time. To understand what social freedom can mean for us now and around here, it is therefore necessary to engage with political legitimacy. The study of what is becoming possible, of the crises of legitimation through which social and political development are expressed - the diagnosis of one’s own times - this, for me, is at the crux of what political theory is.8

For many on the left today, there is something to be done, rather than new theory to produce. To think this, it is necessary to think that there is little that is new about now, or that what is new is not particularly important and therefore does not need to be grasped at the level of theory. For this reason, they don’t seek to foster new generations of theorists who are able to think with the dialectic of limit and unlimit or to make choices rather than act on impulses. Rather, the aim is to instill a scheme of definitions which, once internalized, leads students to engage in a discrete, prefabricated form of activity. The students are limited by this, but their limitation serves the far more important interest of freeing society and is therefore acceptable. In so far as Cutrone was interested in Jacobin, was it because Jacobin seemed as if it could be interested in joining him in the activity he had already decided upon - the creation (or the campaign for the creation) of a socialist party in the United States? If Jacobin became something else instead, does this not suggest that there was something about the times themselves that was not understood? In saying that the Millennial left is dead, or that it is unborn, Cutrone judges it by fixed, prefabricated criteria.9 There’s no room for what’s new.

This is not to say that the Millennial left is doing any good, but it is to say that in so far as the Platypus milieu thinks new theory is no longer necessary, it is mistaken. Its explanations - that the Millennials misread history, or that they have a weakness of will that causes them to retreat from the tasks assigned to them, have a Stoic ring to them. In particular, Walter Benjamin’s idea that theorists are meant to appropriate history so that it “tasks” people screams STOICISM to me, in capital letters.10

No, we do not know how history needs to be understood. We do not know how abstractions need to be conceptualized. We are not unerring Stoic sages, who always know when to say yes or no to this or that. What is needed today is not a doctrine or worldview - it is the continuing capacity to really think, in the first place.

The Enlightenment is exhausted. Its Hellenistic first principles need to be rethought, not for the purposes of rejecting universalism, but for the purposes of generating a universalism that yields something other than acceptance, suicide, and the acceptance of suicide. True social freedom requires the freedom to think outside the bastard box. That freedom cannot simply be asserted or insisted upon - a form of life that supports it should be constructed. And it should be constructed not because somebody says history tasks us with it, but because I think it would (probably) be good, and maybe you do too.

See, e.g., Christopher Brooke, Philosophic Pride, Princeton UP, 2012, pp. 188-202.

Kant, The Critique of Pure Reason, Section III. Of the Interest of Reason in these Self-contradictions, Meiklejohn (trans)., 2010 [1781].

Brooke, Philosophic Pride, pp. 204-5.

Raymond Geuss, A World Without Why, Princeton UP, 2014, pp. 173-4.

It should be mentioned that Aquinas was not the first to do this. Elements of Stoicism and Skepticism can be found syncretized with Platonism or Aristotelianism in Roman, late antique, early Christian, and Islamic thought. Aquinas’ intervention was, however, decisive, in that it was championed heavily by the church. This shaped the way Enlightenment thinkers confronted Plato and Aristotle - as figures belonging to the church, to the ancient regime. It is only at later stages, when integralism and monarchism are marginalized, that it becomes possible to redeem Plato and Aristotle from Thomist appropriation.

See, for instance, my recent discussion with Cutrone in which he makes appeal to the distinction between positive and natural law.

Theodor Adorno, Negative Dialectics, E.B. Ashton (trans.), Continuum, 2007 [1966], p. 149.

Benjamin Studebaker, Legitimacy in Liberal Democracies, Edinburgh UP, 2024.

Cutrone, The Millennial Left is Dead, Platypus Review, 2017; The Millennial Left is Unborn, 2025.

Walter Benjamin, On the Concept of History, Redmond (trans.), 2005 [1940].